I have been fortunate enough to see some truly spectacular cathedrals in my time, particularly in Europe, and even here in the United Kingdom we are very blessed (pardon the pun) to have some of the most splendid cathedrals anywhere in the world.

Some of them date back to Roman Times (St Alban’s Cathedral, for example), while others are nearly a thousand years old and took over a century to build (e.g. Lincoln Cathedral). Like many old and historical buildings they are truly marvels of architecture and engineering, and represent a dedication to a vision and a lasting monument (if also a great accumulation of wealth!). How many building projects today start with a view to completion in decades or even a century’s time? (La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona is perhaps one.)

From a photographer’s perspective cathedrals offer a wealth of opportunities, rife with patterns, lines, features, frames and light; everything an interesting composition could ask for.

Now before anyone suggests that I am exploiting a religious monument for my own photographic gratification, let me say that every cathedral that I have been allowed to photograph in has been extremely welcoming and perfectly happy for me to imbibe its splendour. And while I have absolutely no religious subscription of any kind, I am lucky to have friends of many different faiths and I have the deepest respect for all of them. They know I would never seek to disrespect their beliefs or faith in any way. Furthermore, even though I am focusing on cathedrals here, I look forward to capturing the beauty of synagogues, mosques and temples too.

Right, back to some photography. Cathedrals of all architectural styles, from Gothic to Baroque to Renaissance, are replete with grand structures and cavernous interiors, inviting shots from wide angles lenses to capture the space, to macro lenses to appreciate textures and details. Such a variety of shooting opportunities grants me the impulse to use a variety of focal lengths. And while I may not have the most original collection of shots, cathedrals have stimulated my creativity and trained my eye in more ways than most subjects that I have attempted.

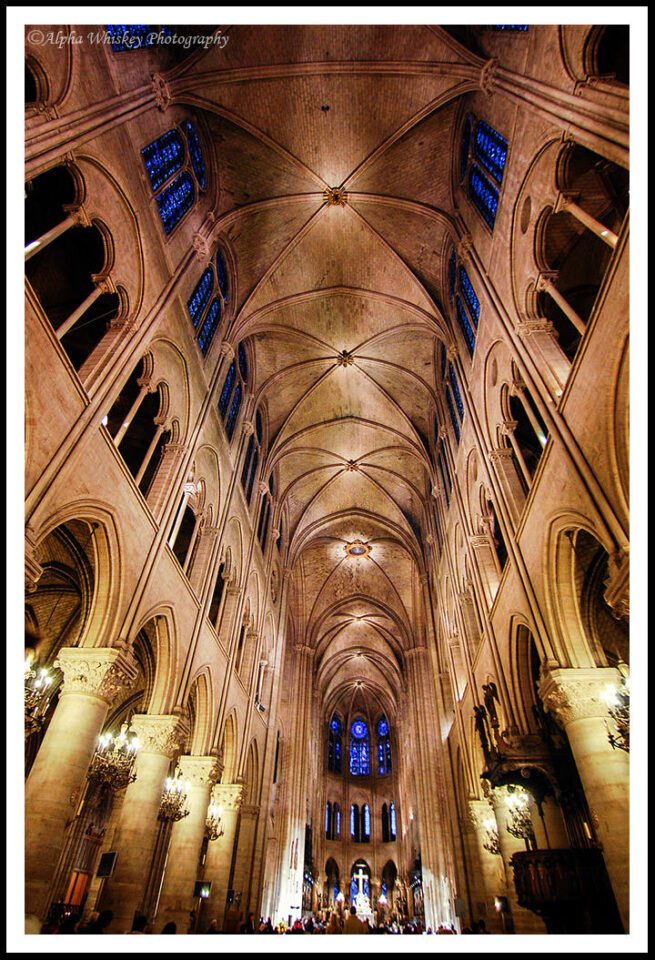

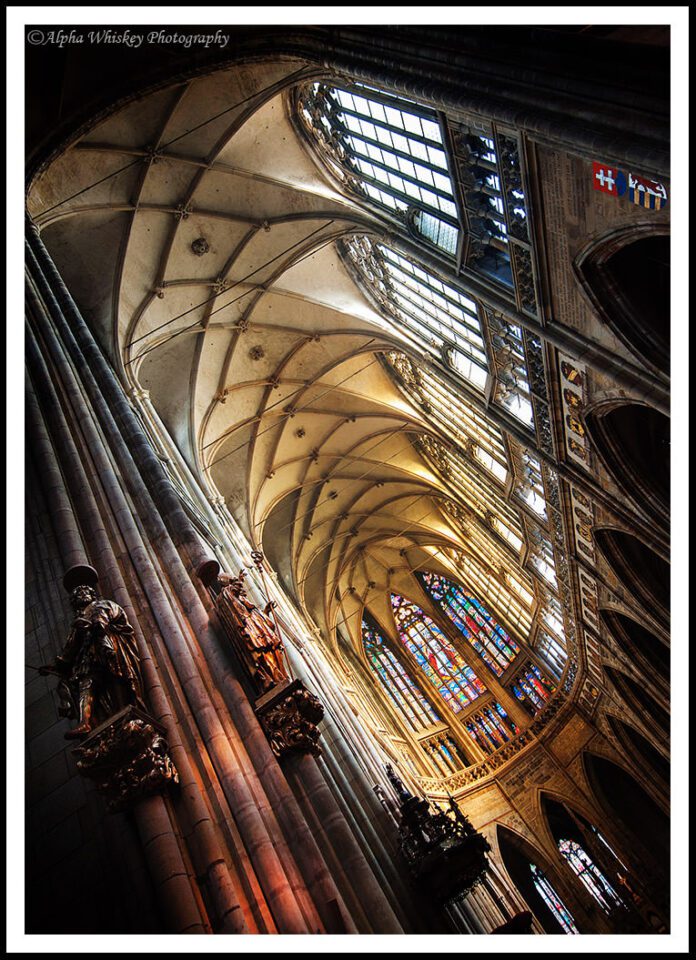

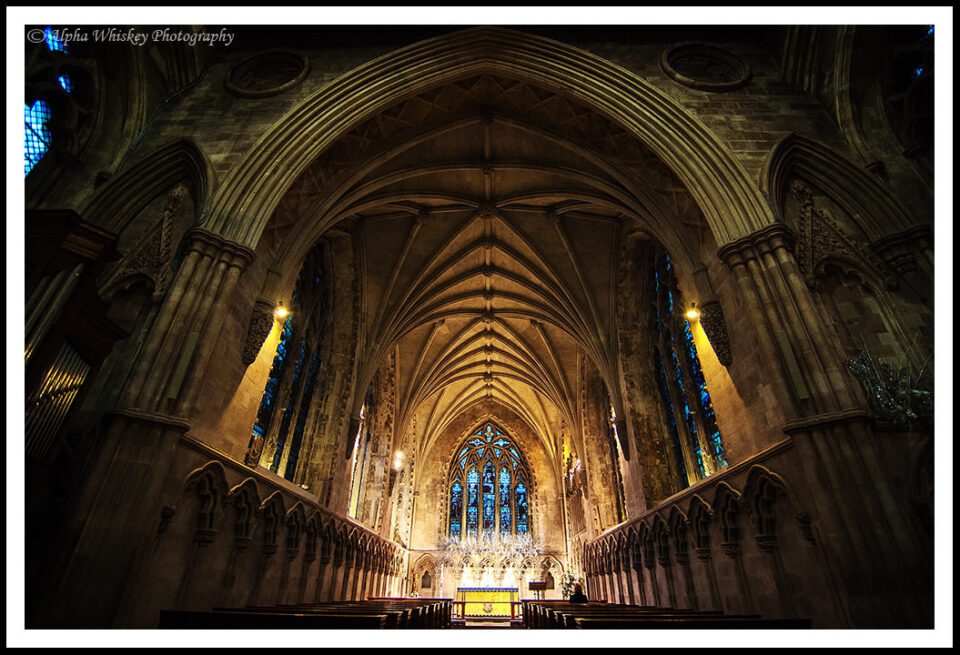

Allow the nave to lead you down its aisle, using the lines of the floor, ceiling and columns to bring you further into the building. The lines themselves can be used alone as a compositional aid, directing the viewer’s eye into the shot.

The columns and their arches provide frames (within the frame) through which the eye can also be drawn through, perhaps to focus attention on a stained glass window or an architectural feature. There are so many spaces and shapes within a cathedral that this is a very useful exercise in framing. Not only can columns and their arches be used as the edges of a frame, but angles within the ceiling or vestibules, or the edges of the transept areas can all be used to frame the rest of the interiors.

(The pulpit and its pillow are here used as part of the frame.)

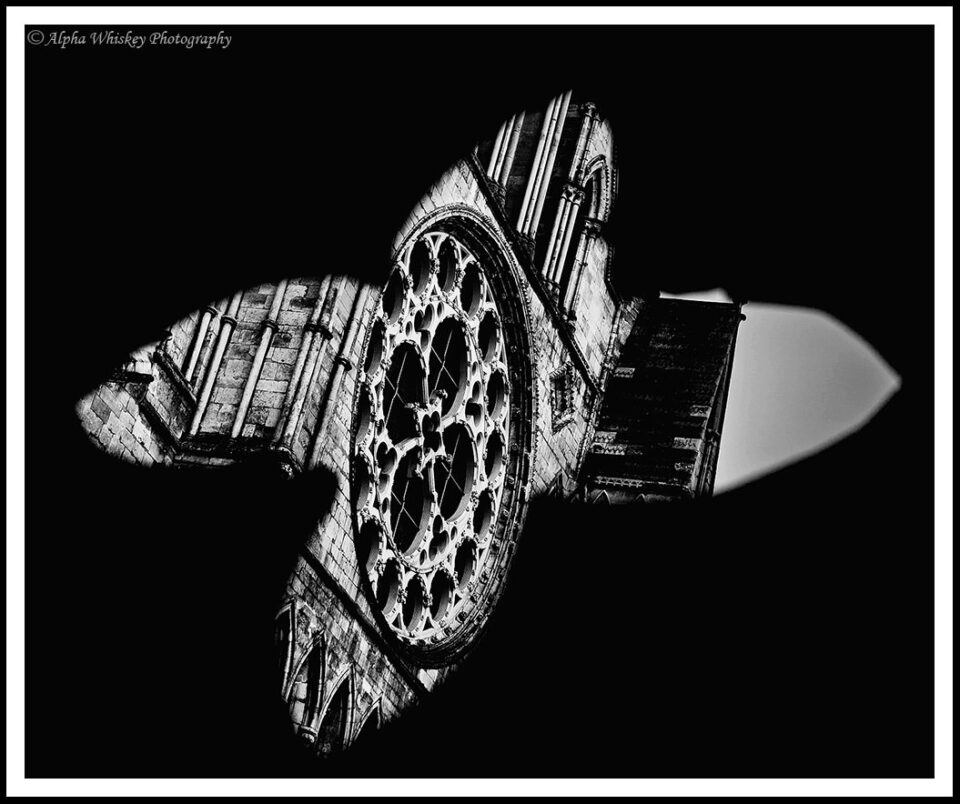

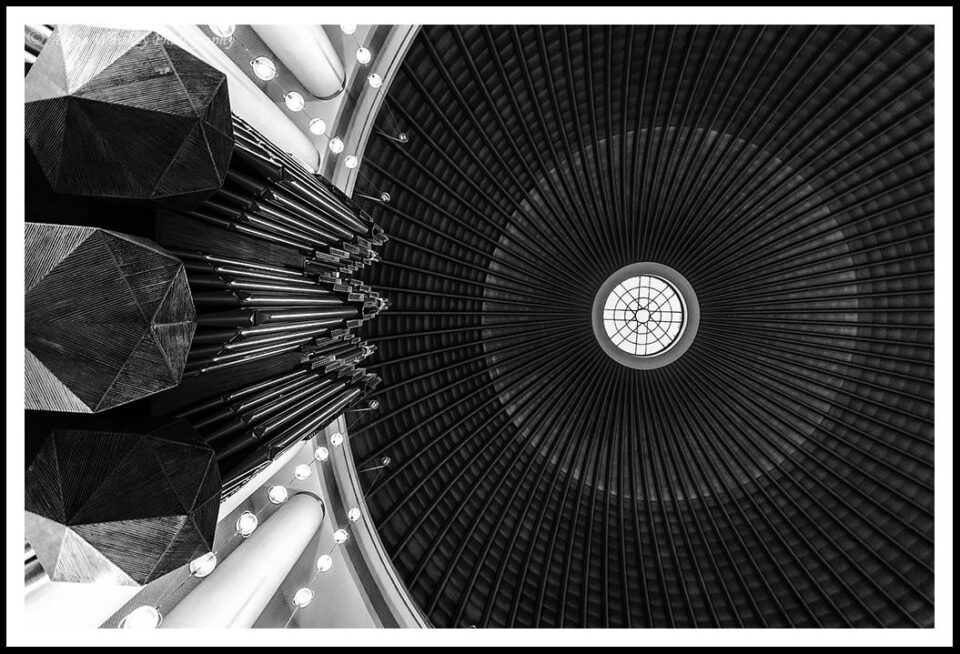

Perhaps the multitude of columns and arches and the regularity of their structure can be appreciated in their own right as an abstract; I find by removing the colour one can reveal the geometric patterns more starkly.

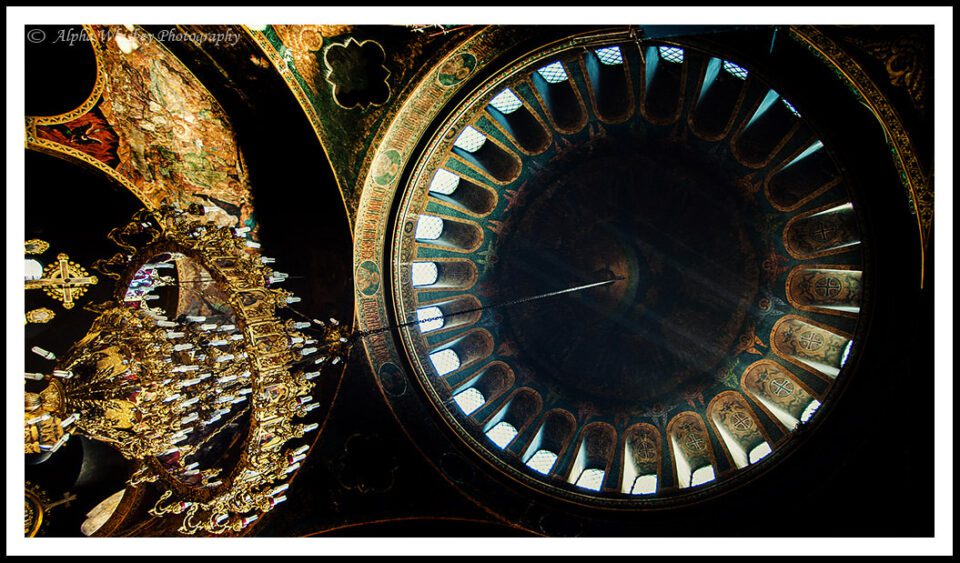

Lighting inside most cathedrals is quite special. Light inhabits small pockets of spaces, adding a glint to the outline of features or statues, or pierces through windows above to beam onto something below.

If the direction of sunlight outside is favourable the stained glass windows can shower their colours onto the floor in front of them, breaking up the concrete grey with a beautiful kaleidoscope of hues. Many of the areas in a cathedral have only selective lighting, providing scope for capturing contrast. Perhaps spot-metering off the lit area can create an abstract composition using light and shade.

Because most cathedrals have these contrasting spaces, from cavernous naves to compact chapels, it does force one to have a greater spatial awareness, and trains one to think of space itself as a compositional element.

Do not forget to look up at the ceiling. Often you’ll find more patterns and directional lines, or simply some magnificent artwork.

Due to their age (at least in Europe), many cathedrals have a multitude of textures and a variety of features (owing to a mix of architectural styles during their lengthy construction). Many of them have very similar statuettes and figurines, for example, the eagle on the pulpit (representing St John The Evangelist). But these details lend themselves to closer inspection and perhaps a rendition with a macro lens. Additionally, there are often small pools or baubles in which one can find appealing reflections (and not just of oneself!).

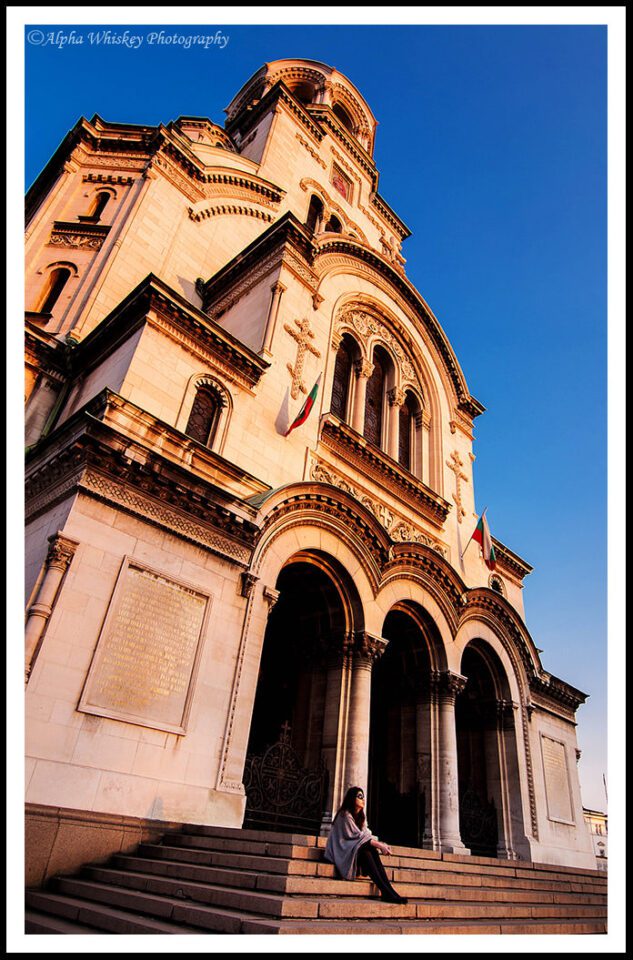

Last but not least, the façade on the outside of the cathedral is worthy of attention. Often a busy and ornate exhibit of carvings, statues and gargoyles, abstract in the sheer amount and variety of the shapes they form and shadows they cast. The magnificent structure of the cathedral itself can be captured against a favourable sky, particularly at dusk.

There are plenty of articles online describing the technical aspects of shooting inside cathedrals, so I won’t presume to surpass them here. This article is about what cathedrals offer as a photographic subject. Needless to say, flashes and tripods are not really compatible with respectful discretion so higher ISOs may be inevitable for hand-held shooting and narrower apertures (unless you’re doing critical commercial work, most cameras these days cope with ISOs of 1600 or below very well). Fast lenses are great indoors but with larger sensors you risk a shallower depth of field wide open (great for individual details but an issue if you’re trying to capture the depth of the cathedral’s interior).

Anyway, perhaps you can see that cathedrals, extraordinary in their own beauty and historical significance, offer tremendous scope as a photographic subject. I’m no expert on architecture but I can appreciate the endeavours and ingenuity of past pioneers to erect these incredible buildings that will probably still be standing long after my worthless body has decomposed. And I am grateful, not only for the opportunity to visit them and learn so much human history, but also for training my eye to see so much better, even without my camera.

I apologise for so many photos. Hopefully some of them illustrate my suggestions.